Introduction: The Jews in South Italy Project (1979-1981)

Jessica Dello Russo (2022)

Through Vatican contacts, International Catacomb Society executive director Estelle Brettman appears to have been introduced to Father Cesare Colafemmina during her extended stay in Rome in 1978. She had planned the trip to be a "fact-finding" mission to evaluate the physical state of the Jewish catacombs in Rome and the prospects for their preservation. Thanks to an introduction by Boston-area friends Frank and Phyllis Gaeta to their cousin in the Roman Curia, Giuseppe Cardinal Caprio, President of the Administration of the Patrimony of the Holy See and later of Economic Affairs, as well as close encounters with Italian archaeologists through her volunteer work in the Museum of Fine Arts and the Archaeological Institute of America's Boston Chapter, Brettman enjoyed, as she put it, "free and unlimited access" to many catacomb sites under Vatican jurisdiction, some, like the Catacomb of Vibia, all but impossible to see today (Brettman to Carol Meyers, 17 March 1979).

Brettman's catacomb tours were complemented by use of the resources and personnel of the Vatican's Pontifical Institute for Christian Archaeology and Pontifical Commission for Sacred Archaeology, housed together in the same building on viale Napoleone III in Rome. Here Brettman tried to consult often with the Secretary of the Commission, Fr. Umberto M. Fasola, B., and Fasola's close collaborators, including Mario Santa Maria, Danilo Mazzoleni, Fabrizio Bisconti, and Carlo Carletti.

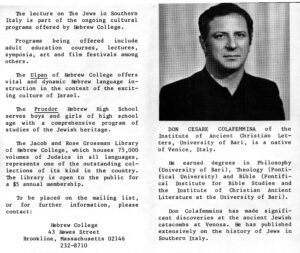

Most likely it was Carletti, a professor at the Institute of Christian Literature at the University of Bari, who put Brettman in contact with his colleague Cesare Colafemmina. Colafemmina (Teglio Veneto 23 April 1933 - Grumo Appula, 12 November 2012) was a diocesan priest and instructor of Biblical Hebrew at the Seminary of Trani, but was distinguished above all for his research on Jews in South Italy. This documentation was not strictly by the books, so to speak, in terms of the written record, but also in the field, through intensive site surveying and artifact study. Largely by his own initiative, and often without institutional support, Colafemmina tried to match up site to text, hearsay to actuality, the Jew to the land from which he appeared to have vanished long ago. Of course, in actual fact, the traces of Jewish Italians (and their descendants) are widely distributed through the Southern Italian territory, if not extensively so beyond a few concentrated spots. Colafemmina, of Apulian descent and a longtime resident in the region, had good reason to believe that more evidence was there, but always under the threat of destruction.

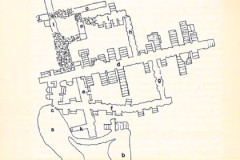

Colafemmina's years of scouting sites appeared to have paid off with confirmation of a rare sighting of a tomb painted with Jewish motifs in an underground cemetery or catacomb in Venosa. A speleologist, Franco Dell'Aquila, had told him about it and together in 1974 they made an extremely risky and unauthorized exploration of a collapsed cemetery corridor until they reached the painted tomb - at the terminus of gallery Q on the map they later drafted from data collected in the attempt - a feature violated, but structurally well-preserved. Colafemmina and Dell'Aquila took photographs in the site, eventually colorized and enhanced, but otherwise authentic.

As the discovery had been made by someone who would have been seen by the Italian Cultural Ministry as an amateur explorer, however well intentioned and informed, it was kept under wraps for a time so that Colafemmina could be sure to reveal it to colleagues in a formal academic setting. He was also genuinely concerned that the paintings would be vandalized just as so much else had been in the cemetery had word got out about the find. Colafemmina did not risk losing hold of such an important secret, however, and revealed the story and photograph at a conference in Bari in 1975 (published 1978).

The announcement was well timed to contribute to the growing attention on the part of Italian Jewish authorities to Jewish cultural patrimony in Italy. The unexpected discovery of a synagogue of the Roman era at Ostia Antica in 1961 had attracted new interest on the part of Jewish scholars to the catacombs of Venosa: now, close to two decades later, with parliamentary debates in course over the fate of the Italy-Vatican Concordat of 1929, it was opportune to assert the historic Jewish presence in Italy predating even that of Christianity.

To arouse government action, it was necessary to create a sense of urgency, not only to secure a legal claim, but also to gain key logistical support from the international Jewish community which had been assisting Italian Jews with rebuilding their institutions after the Second World War. To this end, the Venosa catacombs were presented to the World Jewish Congress in New York in 1977 as a site requiring urgent intervention due to the risk of landslides which according to Colafemmina had put the painted tomb once more out of reach. The focus on Venosa instead of Rome might sound surprising, but made sense at that particular time because the catacombs of Venosa did not involve the question of Vatican oversight, still in place for the surviving ancient Jewish burial grounds in Rome, and there was a good possibility of financing the expropriation of the land parcel on the outskirts of Venosa below which they were found.

From a prominent Jewish benefactor of the AIA, Leon Pomerance, Brettman had been made aware of the WJC resolution and with the encouragement of her archaeologist friends in Italy lobbied long and hard to direct the committee to preserve the Jewish catacombs both in Rome and Venosa. Her trips to Rome were aimed toward getting allies to work with her on the documentation and interpretation of these sites. She was deeply disappointed when the WJC appointed instead Doris Brickner, the wife of Reform Rabbi Balfour Brickner, as Heritage Commission chair. Having recently met with Brickner and Pomerance to discuss "the formation of an international committee to advise on the procedure for fundraising to maintain, and restore the catacombs", she ultimately felt like she had been set aside because of her desire to include scholars who wanted to "work within the existing framework of the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology" (Brettman to Carol Meyers, 12 March 1979). Brickner, clearly, had "divergent views" of the situation, while Pomerance excused himself from all involvement until a new Italy-Vatican treaty was signed. In the end, rather than continuing to play a supporting role in the WJC commission, as Brickner had suggested (D. Brickner to Brettman, 5 February 1980), Brettman founded her own action committee in 1980, calling it at first "The International Committee to Preserve the Jewish Catacombs of Italy" and later the "International Catacomb Society", the name by which it is known today.

With the support of Rome's Chief Rabbi Elio Toaff, Brickner's Heritage Commission went ahead and applied to the Italian government in 1979 for a permission to conduct campaigns of excavation and restoration in the catacombs at Venosa in collaboration with the University of Bari, Colafemmina's host institution. This enabled him to be officially tied to the project of study through the university's Institute of Ancient Christian Literature, directed by Giorgio Otranto. The American archaeologist Eric M. Meyers of Duke University would be the other principal investigator. Funding was in place for a campaign to begin in 1980 that would dig from the surface level down to the "Colafemmina Tomb".

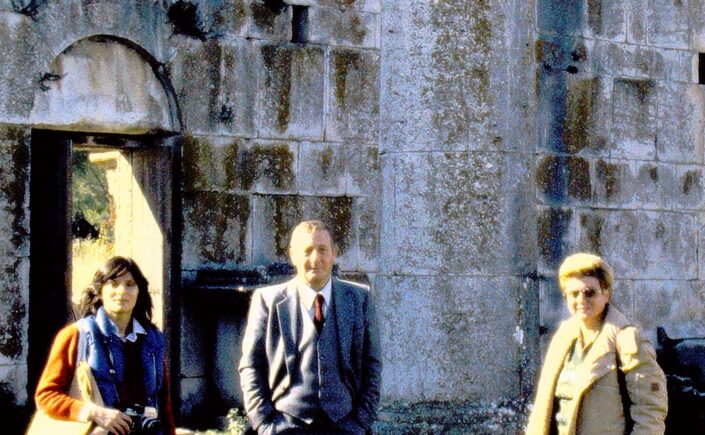

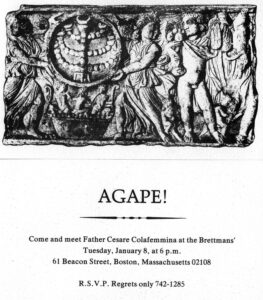

At the same time, Prof. Tom Kraabel of the University of Minnesota was planning a colloquium on Diaspora Judaism at the 100th Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in December of 1979. He sought co-sponsorship to bring in an international panel of experts to speak on "Diaspora Judaism Under the Roman Empire: Recent Archaeological Evidence", declaring to Brettman that "these ancient Jewish communities have been shrouded in darkness for a very long time, as my own research and that of many colleagues has long indicated, but I believe now things are changing for the better!" (A. T. Kraabel to Brettman, 26 September 1979). Colafemmina was invited to deliver the opening address on the Catacombs of Venosa. In her own words, Brettman "finally convinced him to come" by promising financial support for his travel expenses and lecture engagements in other Boston venues (in reality, the AIA paid for the airfare and Brettman for his Boston lodging) (Brettman to Kraabel 11 October 1989). Shortly before Colafemmina's scheduled trip to Boston, Brettman traveled down to Venosa in early November of 1979 in the company of Rick and Bobbie Zonghi, who were helping to set up her catacomb photography show. Colafemmina met up with them there and showed them the catacomb and medieval Jewish headstones reused in the construction of a nearby monastery. Over lunch, Brettman emphasized once more how the trip to Boston could be "meaningful" to Colafemmina and his work. She shared fully his concern about the continued signs of vandalism and neglect in the site, and desire to see the paintings and other features restored to their original brilliance and clarity.

Colafemmina stayed in Boston from 19 December 1979 to 10 January 1980, residing in the Scalabrini Rectory in North Square with other Italian priests. In addition to the AIA colloquium on 28 December, to which was added a last-minute session with artist Letizia Pitigliani on her photographs and paintings of the Jewish catacombs of Rome, Colafemmina spoke in Italian at the Circolo Italiano di Boston and in English at Hebrew College in Brookline, both times on the subject of "The Jews in South Italy" (Gli Ebrei nell'Italia meridionale, sec. III-XI), with emphasis on the communities of Taranto, Oria, Brindisi, and Otranto. He was presented at academic receptions and other meetings Brettman had arranged to launch her new committee and its possible collaboration with Colafemmina on future study of the Italian Jews, in particular the excavation of an early medieval Jewish cemetery in Oria. Colafemmina also must have been witness to "Judaism and Christianity in the Catacombs of Rome", a display of about eighty of Brettman's photographs in the Boston Public Library through 11 January 1980. All the attention put him into an optimistic frame of mind. As Salvatore Fornari reported to Brettman after a meeting with Colafemmina shortly after the latter's return to Italy: "Don Cesare is beaming for his success: he told me all about his conferences and that he is looking forward to returning to the US for further cultural meetings" (S. Fornari to Brettman, 6 January 1980). Colafemmina himself recalled the Boston trip as an "esperienza meravigliosa" for which he owed Brettman "imperitura gratitudine" (Colafemmina to Brettman, 24 January 1980). Meeting Pope John Paul II in person just days after his return seemed to be one more sign of success: as it so happened, the Pope, upon hearing that Colafemmina taught Hebrew Bible Literature in the seminary, exclaimed. "Ah, a Jew!" (Colafemmina to Brettman, 24 January 1980).

Once funding materialized from the WJC to try and open up access to the painted tomb in the catacombs of Venosa, Colafemmina drops off of Brettman's radar in early 1981, something that she was well aware of, commenting that he had been "intimidated" by Rabbi Toaff and the representatives of the WJC (Brettman in letter to S. Fornari, 28 July 1980). Colafemmina did indeed come to see his contact with Brettman as "problematic" to his career, although he continued to assure here that in the field of Jewish Studies in South Italy there was "room for all" (Colafemmina to Brettman 3 April 1980). In particular, he sought funding to restore and display medieval Jewish epitaphs in Lavello; publish every testimony relevant to the existence of the Jewish catacombs of Venosa "as a departure point for all future studies"; excavate the site of a Jewish cemetery at Oria; and survey all of the other material on Jews in South Italy, province by province, for eventual publication. He soon embarked upon a long and productive collaboration with Schlomo Simonsohn's "Italia Judaica" project at the University of Tel Aviv. This provided him with the institutional support to make dramatic life changes and ultimately produce a monograph, The Jews of Calabria, published the year of his death in 2012.

Colafemmina's speech to Hebrew College is presented below.

Presentation by Estelle S. Brettman (1979):

"This evening we have a rare opportunity for Americans to hear a pontifical scholar lecture on material culture which casts new light on the history of the Jews in Southern Italy.

Our guest speaker is a professor of Holy Scripture at the Pontifical Seminary of Apulia and of history at the Institute of Christian Literature at the University of Bari. He is an archaeologist and epigrapher as well as a historian. He was born in the city of Teglio Veneto, near Venice, and received degrees in philosophy, theology, and Biblical Studies. He has published his research in paleo-Christian and Hebrew inscriptions, all of which has contributed to this thorough documentation of the early history of the Jews and Christians in Southern Italy. His latest and very important discoveries in the ancient Jewish catacombs of Venosa were made in 1975.

I am very pleased to introduce to you Fr. Cesare Colafemmina."

Text of Cesare Colafemmina's Lecture, "The Jews of South Italy" (1979):

The most consistent and chronologically extensive evidence of the history of the Jews in the Italian peninsula can be found in Puglia, in Southern Italy. One can only guess as to the origin of the Hebrew presence in Puglia. An ancient Chronicle talks of five thousand Jewish prisoners who were sent to "Taranto, Otranto, and other towns of Puglia" by the Emperor Titus after the destruction of the Holy City of Jerusalem. This information, which can't be verified historically, has the purpose of ennobling the origins of the Jewish communities in Puglia by linking them directly to the Holy Land and to that most tragic and glorious event in the whole of Israel's history.

Attilio Milano, an Italian historian, writes that "probably more than prisoners, Jewish merchants were the first to come and live in Lucania, in Calabria, and especially in Puglia, whose ports faced Greece and the Orient. It is also possible that this first Jewish community, although limited in size, had its origin even earlier than supposed by the Sefer Yosippon, i.e. before the destruction of the Hebrew state."

Not long thereafter, Brindisi has the honor of being mentioned in the Mishnah as being the port of embarkation of Akiba and other colleagues who were returning to Eretz Israel.

The first official information about the Apulian Jews can be found in a constitution issued by Honorius, Emperor of the West, in 398 CE. It is known that in 383, Valentinian revoked the law that exempted Jews from the holding of certain public functions. This had been granted to the heads of the Jewish community during the reign of Constantine the Great (312-337). In 397, however, Arcadius restored this immunity in the Orient.

The Jews in the West decided that they, too, wanted again to be exempt from the holdings of public duties (curial charges), but the Emperor Honorius refused and ordered a constitution to be made, a summary of which was published in Milan in 398, whereby all persons who had to attend to public duties had to fulfill them regardless of their faith. Then the Jews of Puglia and Calabria, i.e., Southern Puglia, protested so vigorously that the Emperor had to intervene directly.

Honorius says:"We have heard that many classes of people in Puglia and Calabria have not been performing their duties, and with the excuse of being Jewish, feel they are exempted by a law issued in the eastern part of the Empire. Therefore, with this constitution, we decree that that law, if it exists, is not valid because in my provinces it is harmful, and we wonder also that those who are in any way subject to public duties, whatever their religion, to accomplish their civic duties to which they are bound."

This document reveals that the Jewish presence in Puglia at that time must have been conspicuous and economically strong, because when the Jews deserted their public duties, the subject of this constitution, many towns in Apulia found themselves in financial difficulty.

From the 4th to the 9th century, there is no further information to be found in the literary sources. There exists, however, good archaeological documentation, especially inscriptions. This documentation is going to be the subject of my speech.

Otranto, for example, situated on the extreme south-east edge of the Italian peninsula, was a busy port in the late empire. The oldest known document attesting to the presence of Jews in the town is a tombstone dated to the early 4th century. We have new information about the Otranto community starting from the 10th century, when, during one of the persecutions caused by the Byzantines, some of its members were killed.

Going back along the Appian Way, we come across Lypiae, today known as Lecce, which is the main town of the province of the same name. Nearby, there was Rudiae, homeland of the Latin poet Ennius. The Jews are documented as being at Lypiae at the end of the 5th century CE. The documentation consists of a funeral inscription that I found in the Jewish catacomb of Venosa. The inscription is dedicated to a certain Augusta, grand-daughter of Symonas, pater Lypinesium. It is most probable that the Lypiensians of whom we are talking established a special synagogue in Venosa. This, as we know, was one of the biggest centers of Hebraism in Southern Italy.

Another important center for Jews in Southern Italy was Oria, a very old town situated halfway between Brindisi and Taranto. As with other Jewish communities in Puglia, that of Oria attributed its origins to the settlement of Jewish prisoners brought over to Italy from Jerusalem after Titus' conquest of the Holy City. The Megillat Ahimaaz, written in the 11th century, is very rich in information about the community of Oria. According to this chronicle, the spiritual life of the community was very intense. When Aaron of Baghdad, a learned representative of Babylonian culture, arrived there in the 9th century, the community appeared to his eyes as an assembly of "tents erected near the water courses that looked like trees growing along the rivers"; he also found established there schools of thought "flourishing like cedar trees that grow near water". Some of the most famous personages to remember from Oria are Amittai, Shefatya b. Amittai, and Amittai b. Shefatiah.

Amittai b. Shefatiah is the author of the well-known poem recited in the burial service of the Roman rite: "Even if a man could live a thousand years and could be all-powerful, he will still descend into the grave without riches and appear before God, the impartial judge." I recognized a stanza of this poem incised on a tombstone.

Situated in Byzantine territory, the Oria community became involved in a violent persecution during the time of the emperor Basil (second half of the 9th century). According to tradition, Shefatya b. Amittai saved the town and four other Apulian centers of Jews from the intolerance of the Byzantine ruler. But this is pure legend. Amittai b. Shefathiah's hymns testify that adults and children were forced to immerse themselves in what he calls "the lurid waters" of Christian baptism and proclaim the Trinity instead of the One. The apparent success of Basil's enterprise in Byzantine Italy is re-echoed in a Calabrian chronicle of the 10th century: "The Jews were baptized in the year six thousand, three hundred, and eighty-two (that is, 873 CE).

After the storm, Jewish life began again even in Oria. It was conditioned, however, by all the events that affected the region. So we see the terror of persecution alternating with that of Muslim raids, common to all. It is not surprising, therefore, that Shefathiah b. Amittai in a prayer asks God to "destroy Seir and his father-in-law", that is, Christians and Muslims.

Oria was taken by the Arabs in 925, and the majority of its inhabitants were killed or enslaved. Some Jews managed to escape and make it to Bari, center of a famous community. For Bari, also, the oldest documentation of Jews is archaeological. In 1922, a necropolis was discovered that consisted of tombs dug partly in the rock and covered with large slabs of tuff. In some cases, even the walls of the tombs consisted of large slabs of sandstone.

In the same area of Bari, in 1923, a small catacomb was discovered that was similar in outline and structure to that of Venosa. A short while after its discovery, the hypogeum was blocked with earth so that a house could be built. The necropolis revealed a few tombstones that came from the open air cemetery situated on the same land where the hypogeum had been excavated. The inscriptions seem to date to the 9th and 10th centuries. They are dedicated to Yosep b. Shamuel, David b. Manasse, Moshe b. Taddai, Moshe b. Eliah, and Eliah b. Moshe. The inscription dedicated to Eliah b. Moshe is very simple, being incised, in a very rough way indeed, on a brick, and containing only the name of the deceased and of his father. On the back, however, there is something we have never seen before in a Jewish context, and that is the title of Eliah b. Moshe as "Istratigos" (strategist). From Classical times, it is the first time a Jew appears to be holding this title. I don't think that the title indicates a strictly religious office and certainly not a military office. It probably indicates a high-ranking representative of the community who had civil and administrative authority.

As we have said, a few refugees of the pillage of Oria in 925 escaped to Bari, which had become Byzantine again in 876. A few years later, Hananel b. Paltiel of Oria started to look for a few of the things that the refugees had saved from the raid on his town. The scholars of Bari contested that, according to traditional teaching, an object belonged to whoever saved it. Hananel's answer is very interesting: Our teachers instruct us to follow the law of the country. A compromise was made, and the refugee regained half of his things, amongst which there was an old copy of the Bible.

The Bari community returns to the scene again a few decades later at the time of the Byzantine emperor Romanus Lecapenus (920-944). This Byzantine emperor had aroused an anti-Jewish campaign that was aimed mostly at the destruction of Jewish books. The Jews of Otranto, warned in time, managed to save the holy books in their possession. However, three learned and pious men were killed: R. Yudah, R. Menachem, and R. Eliah. R. Menachem has also been identified as the poet Menachem Corizzi. The persecution was violent, but very brief. A letter reporting the facts was sent by the head of the Bari community, the doctor Avraham b. Sasson, to Hisdai ibn Shaprut, advisor to Abd ar-Rahman III, Caliph of Cordoba, in Spain.

Returning now to the old Appian Way, we find Taranto, where there is good documentation of Jews in the form of inscriptions that range without chronological interruption from the 4th to the 10th century.

Leaving Taranto, the Old Appian Way goes toward Rome passing by Matera, Gravina, and Venosa, all cities with Jewish communities. Venosa, the home town of great Latin poet Horace, is also famous for its Jewish catacombs. The catacombs were discovered in 1853. The burials were untouched, but the hope of finding hidden treasures brought about the near-complete destruction of the inscriptions and bones of the dead. Almost fifty inscriptions were copied in time, many later destroyed. The inscriptions date to the 4th-7th centuries CE. The languages used in the inscriptions are Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. Considering the relationship of the Venosa Jews to the town council, two inscriptions attribute to two different individuals the title of "patron" or "patronus civitatis". It is known that the title of "patron" was given to rich, influential, and well-deserving people of the town or municipality.

The use of the catacombs in Venosa seems to have ended in the first decades of the 7th century. The Hebrew community started to bury their dead in an open air cemetery that presumably was situated about a quarter of a mile from the town. Most of the inscriptions that come from this medieval cemetery are dated in the range of 808 to 848 CE. The era is that of the destruction of the Temple, sometimes accompanied by that of the creation of the world. The names on these inscriptions are predominantly Jewish, but there are also Greek and Latin names that testify that the Jewish population of the era of the catacombs lived on into the 9th century in Venosa, even after the Lombard conquest.

At the end of the 9th century the Venusian Jewish community seemed to disappear. It is only much later, in the 15th century, that we hear again of Jews in Venosa. I believe that the Arab raids in the region greatly contributed to the dispersion of the old community. We must not forget that the disastrous conditions of the city forced the German emperor Ludovic the Second in 867 to plan for its rebuilding.

Jewish life continued in Apulia until 1541, at which time a public notice was issued that Jews were to be expelled within four months. So ended sixteen centuries of documented Jewish life in Southern Italy. Many Jews of Puglia at that time found refuge on the island of Corfu, where, up to the years preceding the Holocaust, the descendants of these exiles continued to pray in the old dialect of this Italian region, as heard in the prayer recited in the Haggadah of Pesach: "As we divide this bread, so the Saint, blessed be He, divided the Red Sea, so that our fathers crossed it in twelve columns, and He made for them miracles and wonders. May He do the same for us this year, next year in the Land of Israel, free men!" The words of the prayer express the anxiety to return to Eretz Israel, but the use of the Apulian dialect also clearly expresses their faith in the land that was their homeland for centuries and centuries.

(introduction by Jessica Dello Russo, July 2022)