The ICS is looking for a skilled and driven partner to join our team as a part-time Business Manager. Responsibilities include assistance with communications, event planning, and managing the Shohet Scholars Grant program. The full job ad can be found here.

Uncategorized

Sarah Madole Lewis Joins ICS Board of Directors

The ICS Board of Directors is pleased to announce that Sarah Madole Lewis joined the Board of Directors in November 2024. Professor Madole Lewis is an Associate Professor of Art History at Borough of Manhattan Community College in New York City. With a Ph.D. from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, her primary area of expertise is in the art and archaeology of the ancient world with a specialization in Roman funerary art. She has published in the American Journal of Archaeology and Roemische Mitteilungen. She was the recipient of a Shohet Scholar Grant in 2016 for her project New Perspectives on Mythological Sarcophagi and Subterranean Rome. Welcome, Professor Madole Lewis!

Lee Jefferson joins ICS Board of Directors

The ICS Board of Directors is pleased to announce that Lee Jefferson will join the Board of Directors as of November 2024. Professor Jefferson is the Nelson D. and Mary McDowell Rodes Associate Professor of Religion at Center College in Danville, KY. With a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt, his primary area of interest is the development of the Christian tradition and art and imagery of Late Antiquity. He is the author of Christ the Miracle Worker in Early Christian Art (Fortress Press, 2014), a study of the early images of the miracles of Jesus. He is also co-editor of The Art of Empire: Christian Art in Its Imperial Context (Fortress Press, 2015) and editor of Death and Rebirth in Late Antiquity (Lexington Books/Rowman and Littlefield, 2022), a collection of essays in honor of Robin Jensen. Jefferson received the ICS Shohet Scholars Grant in 2013 for the project The Christian Veneration Complex at Khirbet Qana, on which he collaborated with Thomas McCollough. Welcome, Professor Jefferson!

Congratulations to new ICS Executive Officers!

At the annual meeting of the ICS Board of Directors on October 6, the following slate of Officers was elected for a three year term:

- President -- Arthur Urbano

- Vice President -- Nicola Denzy Lewis

- Treasurer -- Pamela Worstell

- Clerk -- Alfred Wolsky

Congratulations to the new Executive Committee and many thanks to outgoing President Robin Jensen and Clerk Jessica Dello Russo for their years of service!

In Memoriam: Patrick H. Alexander

The International Catacomb Society mourns the loss of Patrick H. Alexander, former Society Board member and long-time friend. Patrick was a former director and acquisitions editor for Penn State Press and passionate about the intersection of archeology, art history, and religious studies. Previously, Patrick had been a senior editor at Brill, Walter de Gruyter, and Hendrickson presses. Those of us who worked with Patrick will deeply miss his generous gifts of advice and unfailing support to the work of the Catacomb Society.

Introducing the Shohet Scholars for 2024-2025

International Catacomb Society

Shohet Fellowship Competition 2024-2025

PRESS RELEASE: 3 May 2024

The International Catacomb Society is pleased to announce this year’s recipients of the Estelle Brettman Shohet Competition:

Davide Tanasi (Professor of Digital Humanities, Department of History, Institute for Digital Exploration, University of South Florida) and David Cardona (Senior Curator, Heritage Malta), for their project, “First-time Documentation and Digital Mapping of the Late Antique Hypogeal Site of Binġemma (Malta)".

Caitlin Barrett (Associate Professor of Classics, Cornell University), for her project “Toward an Archaeology of Lived Experience: Modeling Embodied Identities at Pompeii”.

We congratulate these scholars on the quality and impact of their work.

About the Shohet Scholars Program:

The Shohet Scholars Program of the International Catacomb Society desires to support scholars of demonstrated promise and ability who are judged capable of producing significant, original research within the sphere of the Mediterranean world from the late Hellenistic Period to the end of the Roman Empire. Of special interest are interdisciplinary projects that approach traditional topics from new perspectives.

One or more Shohet Scholars will be selected each year and supported for a period of one year. Grants may be made to seed innovative approaches and new ideas or to cover specific expenses or phases of a larger project under the direction of the applicant. At this time, awards in the range of $2,000 to $30,000 will be made.

If you have any questions about the suitability of proposed projects, application procedures, or any other matters related to the Shohet Scholars Program, please contact ICS at: internationalcatacombsociety@gmail.com.

Review: Dinamiche Insediative nel Territorio di Canicattini Bagni e nel Bacino di Alimentazione del Torrente Cavadonna (Siracusa) tra Antichita’ e Medioevo (2016)

Review of: Santino Alessandro Cugno. Dinamiche Insediative nel Territorio di Canicattini Bagni e nel Bacino di Alimentazione del Torrente Cavadonna (Siracusa) tra Antichita' e Medioevo. BAR International Series n. 2802, 2016 (in Italian). Publisher's link.

This volume is structured around a richly detailed presentation of topographical and archaeological data for human settlement in the area of a small city, today's Canicattini Bagni, located about 20 km southwest of Siracuse in Sicily. The author, Italian archaeologist Santino Alessandro Cugno, a Canicattini native, surveyed the territory around the Cavadonna river bed between 2008-2016 for material evidence to better document the chronology of the communities who have lived in these environs since prehistoric times.

The main body of the study concentrates on the period from which most of the ancient monumental remains can be dated, although not precisely, the Late Antique-Early Medieval eras (the book's upper chronological limit is around the time of the Islamic occupation of Sicily in the mid-9th century CE). Due to the very little archaeological excavation that has been conducted in the area to date, most of these monuments are funerary in nature: numerous, fairly accessible, but anonymous, with few exceptions, one of them being a possible menorah incised by a tomb in the interior of a rock cut chamber in the necropolis of Cugno Case Vecchie (tabel XXV.c). This is an amazing detail to recover, considering that the tombs continued to be vandalized and re-used over the centuries, leaving only the bare bones - pun intended - of their architectural form. As it so happens, Cugno and his collaborators were only able to document this decorative (and proprietary) feature in March of 2016 after it was reported in the local press, by means of special illumination techniques to bring out the distinct scratches in the wall, which, from their placement and distinctive design, do appear to be ancient. The menorah might be accompanied furthermore by other motifs common to Late Ancient Jewish proprietary contexts (tombs, community spaces such as synagogues, and on smaller objects, like gems, glassware, and seals) - Cugno cautiously proposes a shofar, an ethrog and perhaps a candle snuffer in the form of pincers - but from the photograph that accompanies the description, it is hard to tell. A tomb used by Jews and specifically marked as such has parallels in other nearby necropoli - the "Grotto del Carciofo" among the "Grotte dei Cento Bocche" at Noto Antica immediately come to mind, and Eastern Sicily holds others. Like virtually all the structures - funerary and otherwise - illustrated in Cugno's survey, this apparently Jewish tomb has never been excavated by archaeologists, though thanks to the efforts of Cugno and his collaborators from the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra della Sicilia Orientale, a helpful site plan now exists (t. XXV, by Gioacchina Tiziana Ricciardi and Azzura Burgio). Curiously, Cugno places this tomb in the section devoted to Medieval monuments - even though it resembles the Late Ancient tombs in the previous chapter.

Under these circumstances, it is much appreciated that the author is honest about the limitations of documenting "dinamiche insediative" (settlement dynamics), because so few of the hundreds of sites described have ever been the focus of an archaeological campaign (Canicattini Bagni has lost out in this regard to nearby Syracuse and Palazzolo Acreide). Yet it is precisely this difficulty that makes this reader wish for a bit more graphic, i.e. visual assistance with the dense data collection. Cugno uses Google Earth Satellite Imagery to pinpoint individual sites, and for our GPS generation, this is a road trip in the making. The structural data, though, would have been helpful to present in tables within the text or in appendices in order to note trends and developments in tomb distribution and typology, an issue raised in many different sections of the book (and which will be also the focus of a future study), and to allow a reader greater familiarization with the list of all the ancient sites in Table II (they are not listed or distinguished in any other way along chronological lines, a seemingly missed opportunity to underline any shifts in settlement). The reader of a topographical survey should experience seeing as well as "believing" - as one certainly does, in the face of so much evidence; otherwise, this rich material must be mined once more to synthesize Cugno's own work (he has so much to say, that even in his concluding chapter, he presents new evidence!). Photos aside, it is a text-heavy work that a few graphic organizers or appendices might have lightened, especially for the sake of the non-Italian reader.

On the subject of evidence, the history of scholarship in the first part of the book is almost exclusively archaeological in nature. Together with the brief chapter on the area during the Middle Ages, this creates a sort of "Dark Ages" within the study for it is not clear how many avenues into archives (monastic/eccleasiastic, private, governmental) have been traveled for documentation on post-Antique land development. Italian bureaucracy though the ages no doubt has left more. In terms of more recent material, Cugno's work does make extensive use of the manuscript notes of Paolo Orsi (1859-1935), from the extreme north of Italy, in what was still the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and a pioneering researcher in the archaeology of his country's extreme other end, Sicily. The quotes from Orsi's journeys into the Canicattini territory - the details of the itinerary, the conversations and first impressions Orsi received of the sites - make more vivid Orsi's official accounts for the annual report of Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità. Though not discussed in Cugno's volume, which does not venture into Syracuse proper, Orsi studied the "Jewish tombs of the Cappuccini" and took note of "many Jewish testimonies on the island" (of Sicily). Like Cugno, Orsi saw this "Jewish evidence" originating in the east, in Syria-Palestine. New Testament peregrinations aside, it is clear that Eastern Sicily was populated by Jews in the Ancient and Medieval periods: material traces of their presence survive in the form of epitaphs, tomb decorations, small objects, and - possibly - one or more communal properties of the later middle ages featuring ritual baths. Like Orsi a century ago, we hold on to the hope that more Jewish artifacts will eventually be brought to light, as Cugno and his colleagues now appear to have done with the example of the menorah graffito at Cugno Case Vecchie. Together with original color photographs, a conscientious review of prior studies and new research, and a strong sense of mission to put his hometown on an equal footing with the neighboring sites of Syracuse, Palazzolo Acreide, Noto Antica, and other touristy towns, this discovery makes "Dinamiche Insediative" an exceptional point of departure for future exploration of Canicattini. Clearly, Cugno has awarded himself a life contract for such work.

- Reviewed by Jessica Dello Russo (7 September 2016)

In Memoriam: A. Thomas Kraabel (1934-2016)

ICS marks the passing on 2 November 2016 of Professor A. Thomas Kraabel, who collaborated with ICS founder Estelle S. Brettman on the organization of the international panel "Diaspora Judaism Under the Roman Empire: Recent Archaeological Evidence," at the American Institute of Archaeology's Annual Conference in Boston in 1979. Invited panel speakers were Prof. Cesare Colafemmina on the Jewish Catacombs of Venosa; Prof. Dean L. Moe on the synagogue at Stobi; Prof. A. T. Kraabel on Jewish Communities of Western Asia Minor; and Prof. Eric M. Meyers on Gailean Synagogues and the Eastern Diaspora, with Prof. Jacob Neusner as respondent. As AIA Boston Program Director, Brettman helped to raise funds for Prof. Colafemmina's travel expenses and speaking engagements around Boston. Her exhibit, "Vaults of Memory: Jewish and Christian Imagery in the Catacombs of Rome," (link) also made its debut at the Boston Public Library at this time as a featured event during the AIA conference. ICS reprints below Kraabel's AIA panel abstract, both as a tribute to his fine scholarship and as a sign of support for his view that much work remained to be done.

"The study of Diaspora Judaism, the Jews under Roman rule but outside ancient Palestine, has long been only a "related field" for classical archaeology - which stresses "classical" sites and problems - and for Biblical Studies and Jewish Studies, which tend to focus on other geographical areas or time periods. The latter also favors other kinds of evidence, chiefly religious texts, while the data for Diaspora Judaism are chiefly archaeological.In the last quarter-century, several major new sites have been discovered, and the reexamination of previously known evidence has progressed substantially. Presently, major initiatives are underway to preserve and record endangered sites and other evidence from the Diaspora, chiefly in Italy and Egypt. Beginning with the new data, this colloquium attempts to view Diaspora Judaism in its own right, in order to more fully understand it as at the same time (his emphasis) an important phenomenon of the society of the Roman Empire, and an authentic and creative expression of ancient Jewish culture and religion. The newest evidence is coming from Italy, where some of the most ancient Diaspora communities were located; the major presentation, by Prof. Cesare Colafemmina, deals with some of this material, nearly all not yet published. The next three speakers summarize the results of their own excavations and related sites. Prof. Neusner, dean of academic Jewish studies in North America, assesses the new archaeological evidence against the background of the larger context of the Judaism of Late Antiquity, known previously chiefly from rabbinic writings. The concluding discussion permits responses from the previous speakers and from the floor."

In Memoriam: Former ICS Director Nitza Rosovsky (1934-2023)

The International Catacomb Society remembers with affection and gratitude Harvard Semitic Museum curator Nitza Rosovsky, a former ICS director. Mrs. Rosovsky passed away in Cambridge, MA on 29 December 2023. Her obituary is here. In addition to arranging for ICS lectures in the newly inaugurated Rosovsky Hall at Harvard Radcliffe Hillel, Mrs. Rosovsky was the guest curator for the Bible Lands Museum's showing of "Vaults of Memory: Jewish and Christian Imagery in the Catacombs of Rome", coordinating the redesign and installment of exhibit components with museum directors and staff and planning a special program of events to mark the Bible Lands Jerusalem's second anniversary celebrations in conjunction with the exhibit opening in Jerusalem in the spring of 1994.

Jessica Dello Russo interviewed for Archaeology Magazine article on Jewish Catacombs of Rome

Journalist Sara Toth Stub interviewed ICS director Jessica Dello Russo for the article, "Secrets of the Catacombs" in the January 2024 issue of Archaeology Magazine. Below is the complete transcript of her interview with Dr. Dello Russo on 6 September 2023, quoted in part.

STS: What is the overall significance of the Villa Torlonia catacombs? Are these different from other Jewish catacombs in Rome?

JDR: The catacombs of Villa Torlonia are located about a kilometer from the ancient walls of Rome, near the ancient trajectory of the via Nomentana and a crossing, similar to the via Spallanzani of today. Several historic or named Chrisitan cemeteries were on the same highway, including one now open to the public at Saint Agnes Outside-the-Walls. I mention the Christian sites to emphasize that the Jewish catacombs of Villa Torlonia, while apparently self-enclosed and not known to connect to other cemeteries or tomb enclosures in the surrounding terrain - although the actual terminus of a small number of galleries is not yet known - would have been located in the general area of a Roman-era roadside necropolis, not exclusive to Jews, although nothing of this ancient development is currently visible in the site. The land has been a public park only since 1978 - before then, for nearly two centuries, it was extensively landscaped and built upon by the Torlonia family as a showpiece estate - with conspicuous fake ruins, even a modern cave decked out to look like an Etruscan tomb. Whether or not the family was actually aware of the catacomb is not clear, but we know that they closely controlled their public image, and tried to suppress the rumor that, because of their non-Italian origins and extreme wealth, they were converted Jews. The Jewish artifacts reportedly in their possession - in what became and still remains one of the largest privately-owned collections in the world of ancient art - remained for the most part unpublished until the early twentieth century, and nearly all are unaccounted for today. When the Jewish catacombs were finally revealed in a building site on the property in 1919, Giovanni Torlonia, who later rented the estate to Mussolini, made a point of saying that he regretted that they had not turned out to be Christian.

The overall significance of these underground cemeteries for Jews is that they are virtually the only surviving testimonies of a distinctly Jewish material culture in Ancient Rome that employs pretty much the same motifs and expressions seen as markers of Jewishness in all parts of the Late Ancient Mediterranean and beyond. Artifacts labeled with the representative menorah, sometimes accompanied by other emblems of Jewish ritual practice, have come up in other sites around the city, even the Palatine itself, but the catacombs have produced the bulk of the information for what is currently known about Jews in the city itself - although the archaeological traces of a synagogue complex in nearby Ostia Antica have helped to flesh out some of the context of Jewish communal activity that is still missing from Rome itself. We wouldn't know about these people or even the names of the synagogues they frequented without the evidence from the Jewish catacombs. Literally, they make history.

What makes the catacombs of Villa Torlonia quite special can be expressed in terms of the nicknames given by modern excavators to the two distinct excavation projects that over time created the cemetery network that we see today, each one excavated from its own entrance point into a different level of the underground. One region - two regions, actually, but both depending on one point of entry - was known as the "catacomb of inscriptions" and the other was the "catacomb of the pictures". The inscriptions, many painted directly onto the rubble and mortar seals for the shelf-like tombs, and written for the most part in Greek, give us personal names, loving attributes, good wishes and blessings, and, in some instances, community office titles, including one still very debated term that could be read as the "archigerusiarch", maybe the leader of an assembly of elders. There is even some evidence of Hebrew, which is actually quite rare to find in epitaphs made in Rome during this period, although all the cemeteries in question have been heavily vandalized. An early visitor to the newly-discovered site in the 1920s, the American Classicist and Reform rabbi Harry J. Leon put it this way: It was deeply moving for him to read the epitaph of a Jewish woman from almost two thousand years ago and still see her bones right there in the tomb. Like Leon, Jews today feel strongly about this evidence of a continuous presence of Jews in Rome in light of so many centuries of oppression to the point of near-elimination in very recent times.

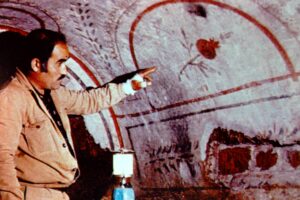

The wall paintings in the other region of Villa Torlonia are even more extraordinary, and it is really necessary to see them in person to appreciate the brilliant colors and vivid style of depicting for the most part Jewish motifs connected to synagogue liturgy and annual festivals like Rosh Hashanah and Tabernacles. Pictures, even photographs depending on artificial lighting, don't do them justice! We don't know at present who was originally buried in these beautifully decorated tombs, all found in one gallery near the staircase to the grounds above. The tomb style is that of the fourth century CE, so these are individuals who lived in a time when Christianity was becoming more and more of a public institution in Rome. The level of tomb decor would indicate Jews of means, perhaps patrons of their community, but, as time went on, the painted tomb niches themselves were filled up nearly to the top with later tombs so that little of the original decoration could be seen until modern excavators removed the walls of the later tombs and exposed the paintings once more.

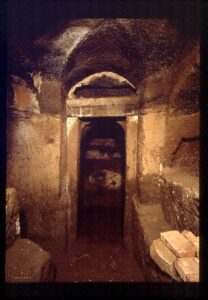

The Villa Torlonia catacombs also have some very distinct features in their planning and tomb design. Even within the site itself, there are marked differences in appearance between regions: why, exactly, I don't know, maybe there was a different dig crew employed or a different plan adopted to sell off burial spaces within the site. The upper galleries have around thirty tall arched wall recesses; the lower galleries virtually none, unless you count those with a very low arch, part of an arrangement when more than one burial was made in a single wall slot. The lower regions also exist side by side, but were originally excavated separately: that is, a landing was created within the original access stairway from the ground to area E to allow for a branch staircase to lead into a whole new network of galleries (area D). This might indicate a permission or land acquisition to expand into the zone, but it is interesting to see that access to both regions was through this one stairway, only. But it is hard to read a "Jewish" meaning into elements of structural design: it might have more to do with property limits, pre existing tunnels, and other circumstances.

Regarding its design, the catacombs of Villa Torlonia have a number of features in common with non-Jewish catacombs in the areas northeast of Rome along the via Nomentana and elsewhere: including the marking up of some of the gallery walls with designs in lime to map out the burials and intersections and the frequent use of very basic materials to seal up the tombs. The diggers knew what they were doing. The site might even have been a prefab arrangement on the part of cemetery developers which Jews were able to obtain for use by members of their community, as there are signs especially in the upper catacomb that a lot of the monumental space was never really used to its full potential in terms of the added expenses of tomb style and decor, and later extensions of galleries in the site show a more haphazard type of tomb distribution. A lot of the tombs were created in a very simple style, wall slots closed by masonry. This was carried out very carefully and in many galleries with great regularity as to the size and spacing of the wall slots. These details help to read a very interesting history of development of the site. All the same, there is no question that all the spaces created were ultimately used for the burial of Jews - if there were "interlopers", that would be at a late date, as might be the case for a tomb made in one of the stairwells, and the presence of lamps with Christian symbols like the Chi-Rho might just point to the sheer necessity of artificial lighting in the complete darkness of the catacombs - anything that was handy, as the Chi-Rho style certainly was. There were also small objects attached to some of the wall tombs that were clearly personal objects and on the whole not associated with Jewish ideas in any way. That being said, the clientele for the Villa Torlonia catacombs were Jews seeking burial next to other Jews - as is sometimes spelled out in the epitaphs their wish was to sleep "among the holy ones" or "among the just" . They are remembered in terms of their goodness and generosity toward the community, and love of the Law.

STS: Are Jewish catacombs in Italy well-understood, or are there many questions remaining?

JDR: The big elephant in the room is - accessibility! There are Christian catacombs regularly open to the public at around 10 euro. To enter the only Jewish catacomb in Rome currently open to the public, in the former site of the Vigna Randanini, one spends more than ten times that, unless one has the opportunity to join a guided tour of up to 15 people. Ideally, a public monument should not cost so much to tour - but the catacomb in question is on the grounds of a private property and a custodian must be paid to open the site. The Villa Torlonia arrangements promise to be quite different, although to date the catacombs themselves remain off limits to all but the most privileged insider. From what I understand, the Jewish community of Rome hopes to train its own guides to work at the site, similar to what you would find in many of the other catacombs in Rome open to the public. In a somewhat ironic twist, Mussolini's underground bunker in the Villa Torlonia was open to the public before the cemetery was: of course, it is smaller, of fairly recent construction, and does not contain bones!

For those specialists fortunate enough to be able to examine the Jewish catacombs and any material removed from them in the past - mainly to museum galleries and storerooms - there are, indeed, big questions to be addressed and next steps to take. At the top of the checklist, making images of the inscriptions and of other cemetery features widely available. Even if the archaeological authorities don't want Jewish catacombs turning into another Coliseum of tourism - being wholly underground, their microclimate simply can't handle that volume of visitor traffic, and people throughout the centuries have had a bizarre tendency to steal the bones - there are no negative and invasive consequences in providing digital reproductions of the artifacts, many of which still await publication. Recent study of the Jewish catacombs of Venosa by the University "L'Orientale" in Naples under the direction of Prof. Giancarlo Lacerenza is a good example of systematically documenting the architecture and artifacts and rendering this material open access.

The fact is, without targeted investment in Geo Radar surveys, 3D mapping and other strategic approaches, and - yes, ground excavation and historical osteology analysis - remember, a rabbinical ruling has allowed this now to be done on human teeth - there is a lot of information that will continue to escape us. It's not just the cost of highly specialized labor and instruments. The problem also involves the reality that many Jewish catacomb sites are on privately owned land, and, apparently the property owner still has a lot of influence over what can take place. These private citizens are legally bound not to further obscure or cause deterioration to the monument in question. At the same time, and perhaps understandably, they don't appear to welcome the disruptive presence of tourists. Even so, this sense of ownership over the site has frustrated serious study - nothing like having a guard dog or an untethered bull going at you to force a quick exit!

Leaving aside for the moment the question of the origin of this type of cemetery development in Rome - we'll speak more about that in a minute - beyond better documentation of and accessibility to these sites, they should not be studied in a "bubble", that is, just as information about Jews. These people represent Ancient Rome. Don't take the statistics from these burial grounds as exclusive indicators of the community - they were part of a civil society and were representative of it as well. And it's pretty clear that not all Jews were buried in catacombs!

STS: Is it possible to say where the origin of catacomb burials in Rome comes from? Does this come from Jewish practice?

JDR: I've traveled to the Middle East and other parts of Italy to consider this issue carefully, being aware of my own bias in the matter, having been trained in the Vatican's archaeology program, from which I obtained a Ph.D. in archaeology in 2022. My take after studying examples of rock-cut tombs for Nabateans, Jews, Phoenicians, and other Semitic communities, and those of different communities on the Italian peninsula and islands, is that local know-how created the catacombs on the scale that we know them today - notably those reaching truly colossal dimensions after being developed on multiple levels, with interior connections as well as external points of access, often from pre-existing tomb enclosures, used for hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands of burials if not more. Given the land use already where we find catacombs, it would have to be something of an entrepreneurial opportunity more than a cultural or ideological choice - although it might be a combination of the two. Rome's malleable volcanic soil provided the opportunity to carve out and articulate tomb designs in amazing ways, with many options for customization for familial or other group aggregations, as we see just in the Jewish catacombs alone. The "fossores" or gravediggers provided these services, and it was a real business. The Jews of Villa Torlonia had access to this type of specialized labor, and furnished the site according to their needs and circumstances. Other underground cemeteries used by Jews in Rome have very different layouts and tomb designs, although with many points in common, including the epigraphic language and overall concept design. This type of rock-cut burial enclosure was made in different areas of Italy in suitable geological strata centuries before the catacombs came into existence. However, it was on a far more limited scale, more in line with what was being also done in the Mediterranean East for families of means. In fact, some catacomb areas connect with or develop from similar "closed" tomb networks for intimate use that date from perhaps the end of the second century CE, certainly by the first decades of the third. The structural evidence suggests that Jews and Christians adopted the "open" style catacomb with less hierarchical distinctions, a certain monotony of planning, if you like - around the same time, within the chronological framework cited above. I know there have been radiocarbon dating experiments that suggest otherwise for Villa Torlonia, and I have my fingers crossed that the recent excavations in the site to open it to the public on the part of Rome's Archaeological Superintendency have included the careful recording and analysis of the entrance points in order to provide the necessary data as to the sequence of building in the site - otherwise the "primacy" of the Villa Torlonia catacombs must remain in my mind a theory.

STS: I would like to speak briefly about the history of the Jewish community in Rome, especially during Late Antiquity----and how Jewish catacombs help us understand this time period.

JDR: As I said, the catacombs pretty much provide what we know about Jews in late ancient Rome, with the synagogue and tomb markers from nearby Ostia important points of confrontation. Again, it's important not to see this evidence as monolithic - in fact, as is oft-repeated in specialist studies, had we not found certain epitaphs in a Jewish catacomb site, it would be well-nigh impossible to consider them within the corpus of Jewish epigraphy. Maybe for this very reason, despite the presence of Jewish cemeteries in different areas of the suburbs of Rome, we're missing so many Jews, especially from the late republican and early imperial eras, when they are already documented as living in the city, because they were buried in so-called "neutral" settings and what we commonly call "catacombs" did not yet exist. Seeing catacombs as a developing trend in late antiquity reminds us to open our eyes and our minds to finding Jews in other places - not as "lapsed Jews" or as "assimilated Jews" but Jews in virtually all sectors of Roman society, as they seem to have been. Because of their position well below ground, the catacombs kept their structural integrity somewhat more complete than that of many structures at or near surface level. The type of information we can retrieve from them is what under most other circumstances would not have survived.

Terminal point of a gallery closed off in wall of masonry in the lower catacomb of Villa Torlonia, Rome.

Detail of a wall tomb with an arched roof in a gallery of the lower catacomb of Villa Torlonia, Rome.