Celestial Transports (Chariot - Peacock – Sun - Moon). Excerpt from: Estelle Shohet Brettman, Vaults of Memory: The Roman Jewish Catacombs and their Context in the Ancient Mediterranean World, with Amy K. Hirschfeld, Florence Wolsky, & Jessica Dello Russo. Boston: International Catacomb Society, 1991-2017 (rev. 2024).

In many ancient civilizations around the Mediterranean, chariots drawn by horses, fanciful Pegasus-like equines, or griffins (part eagle, part lion) were associated with the solar deities and with strange lands. Thus these creatures were appropriate psychopomps for their divine, heroic, or prophetic passengers.

According to Greek myth, Zeus (the Roman Jupiter), supreme divinity of the Greek pantheon, took the form of an eagle and carried off Ganymede, the beautiful Trojan youth, to the abode of the gods on Mt. Olympus. In later iconography, the legend became an allegory for the spiriting away of the soul from the body: "... and how I bare you on eagle's wings and brought you unto myself" (Exodus 19:4).

Divinities and mortals have been conveyed to the realms beyond the earth and back home on the wings of eagles in literature and art from the period of the third millennium. Plato's sepulcher in the Kerameikos is reputed to have borne the image of an eagle to indicate that his soul had been transported to Olympus.[1] Oriental kings were alluded to as eagles in their ability to transplant the royalty of Israel (Ezek. 17:3-5, 7, 8). The powerful bird marks Jewish burials in the Late Ancient catacombs of Beth She'arim, Israel.

Fig. 1. Soaring Pegasus: The fabulous winged horse, which bore Bellerophon in his contest against that hybrid beast, the Chimaera, and carried Perseus in his victory over the monster attacking Andromeda, became a metaphor for the contest of the forces of good against evil. In the Classical world, horses were emblems of the sun, since they drew the chariots of Helios and Apollo. In Judeo-Christian thought, they were related to the ideas of ascension and apotheosis. The painting of Pegasus in the Vigna Randanini catacomb is in the summary "tachiste" style like other paintings in the same site, and yet there is an esprit and a freshness of observation of nature that gives these images a sense of immediacy and considerable charm. Wall painting in a chamber near the entrance to the catacomb of Vigna Randanini, Rome.

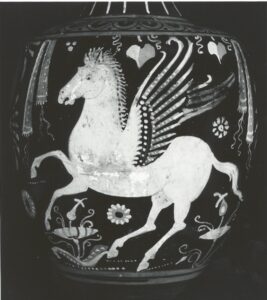

Fig. 3. DAPICS n. 3561. On an Apulian oinochoe, or wine jug, of the fourth century BCE, Pegasus prances over flowers, which include the exotic lotus, emblem of constant renewal for the ancient Egyptians. The scene is surrounded by the traditional vine leaves, funerary fillets, and rosettes. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.

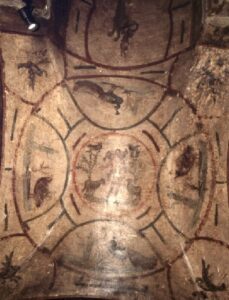

Fig. 2. Mosaic of Christ as Helios: In this scene a character possibly meant to represent Jesus as Helios, the Su, with a seven-rayed nimbus, ascends to a celestial vine arbor in a chariot drawn by four rearing white steeds, a figuration recalling ancient representations of Victory. Roman emperors often identified themselves with Sol Invictus, just as earlier Hellenistic rulers emulated the image of Helios by wearing radiate crowns. Seven was a mystical number for many cults; a well-known instance is the sacred seven-branched candelabrum of the Jews known as the menorah. The paean of Akhenaten to his one god, the Sun-god Aten, also touches upon the theme of eternity: "Thy rising is beautiful, O living Aten, lord of Eternity; Thou art shining, beautiful, strong; ... thy rays are cast into every face, thy glowing hue brings life to hearts..."[2]

The mosaic decorates the vault of the Mausoleum M of the Julii in the Vatican necropolis. Pre-Christian in origin, the mausoleum was originally built by the parents of Julius Tarpeianus, who died in the mid-second century CE before reaching the age of one year and ten months. At the beginning of the third century, it became a Christian burial place, either because the original owner converted to Christianity or because it was sold to a Christian. It was at this time that the mosaic was executed in the mausoleum vault. Mosaic in the vault of Mausoleum M in the Vatican Necropolis, Vatican City.

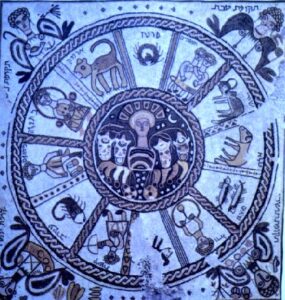

Fig. 4. Helios among the Constellations: A radiate crowned Helios driving his quadriga is delineated in primitive perspective. His journey through the starry and moonlit heavens becomes the center of a zodiacal wheel which in turn is framed by a square with four seasons embellishing the corners. The epigraphy is in Hebrew. In Genesis 1:14-16, God created light in the heavenly firmament: "And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night; he made the stars also." Mosaic floor of a sixth century CE synagogue, Beth Alpha, Israel.

Fig. 5. DAPICS n. 2953. Winged Sentinel: A forbidding griffin guards the end of this sarcophagus with Dionysiac themes on the front. From the catacombs of Villa Torlonia, Rome.

Fig. 6. Ascension of Elijah: On the left of this sketchy, impressionistic pastoral setting, the Jordan gushes forth from a grotto. Seated on a rock on the right, and leaning on his plough, a peasant watches an unusual drama: Elisha, clad in an animal skin, with arms outstretched, prepares to receive the mantle of succession tossed by Elijah, who drives off in a chariot drawn by four soaring horses. ".... behold there appeared a chariot of fire, and horses of fire, .... and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven. And Elisha saw it, and he cried, my father, my father, the chariot of Israel, and the horsemen thereof" (2 Kings 2:11-12). Painting in the lunette of an arcosolium in Chamber B of the Catacomb of via Dino Compagni, Rome.

Fig. 10. DAPICS n. 1863. An Emperor's Optimistic View of the Future: The Roman Emperor Titus is borne aloft by and eagle in the interior vault of the arch of Titus in Rome, erected after 81 CE.

Fig. 7. Preparations for the Journey: A stately but fierce griffin grips a dead youth. Greek intaglio, Chalcedony scaraboid, early 5th century BCE.

Fig. 9. DAPICS n. 2036. The Abduction of Ganymede to Olympus: A majestic Zeus carries off Ganymede, who clutches a cock, a love gift. The Trojan prince became the cupbearer of the gods. Terracotta group, ca. 475-470 BCE, Olympia, Greece.

Fig. 8. A Greco-Roman View of the Same Scenario: Elegant stuccowork decorates the vault of the first century CE subterranean basilica of Porta Maggiore in Rome, which may have been constructed for use by one of the mystical sects flourishing during this era, possibly the Neo-Pythagoreans. Here, a more pragmatic Ganymede grasps an elegant pitcher, for potential use in his future calling, as his is propelled aloft by the sovereign god of the Olympians, who bears the torch of immortality in his left hand. His upper torso has been destroyed.

Fig. 12. SEVERUS "And the Lord Seized Her Inviolable Soul": An inscription found in a double chamber with arcosolia and light well reads: "By the order of his Pope Marcellinus, this Deacon Severus, grateful, has constructed for himself and his [family' a tranquil sojourn in peace, in which to keep, for a long time, the beloved limbs in the slumber of peace for the Creator and Judge. The maiden Severa, a delight to parents and to family, surrendered her spirit on the eighth day before the Kalends of February (24 January); upon her the Lord bestowed from birth extraordinary wisdom and skill. Her body, resting in peace, is buried here until it rises again and the Lord who seized from her hallowed life's breath her pure, chaste, and at all times inviolable soul, restores again her spiritual glory. She lived nine years, eleven months, and fifteen days: thus she departed from this life." Epitaph carved on the reused fragment of a marble transenna from a pagan tomb in the Catacombs of S. Callisto, Rome. It is notable because it is the first recorded mention of the Bishop of Rome as "Pope" (Marcellinus, 296-304), and also for its references to specific architectural and structural elements of the catacombs (DAPICS n. 0950).

Fig. 13. Ascent: The only painted evidence of the Zeus/Ganymede theme identified by Estelle S. Brettman in the catacombs of Rome. Pendentive painting in chamber, Catacombs of S. Sebastiano, Rome (DAPICS n. 1154).

Fig. 14. DAPICS n. 1433. "She Will Rise to Eternal Life". A Latin inscription in poetic meter from the catacomb of Monteverde bears the poignant tribute of a mourning husband to his young wife which integrates concepts of immortality in vogue during the Greco-Roman period. The text reads: "Here lies Regina, covered by such a tomb which her husband set up for her as fitting to his love. After twice ten years she spent with him one year, four months and eight days more. She will live again, return to the light again, for she can hope that she will rise to the eternal life promised, as is pledged to the worthy and the pious, in that she has deserved to possess an abode in the hallowed land. This your piety has assured you, this your chaste life, this your love for your family, this your observance of the law, your devotion to wedlock, the glory of which was dear to you. For all these deeds, your own hope of the future is secure. In this your sorrowing husband seeks comfort."

Fig. 11. Ascent to the Celestial Regions - Under an arch decorated with a guilloche border, an eagle ascends through the seven known celestial spheres, encircled by a symbolic wreath. Two ungainly peacocks perch on the gabled roof which is supported by a pair of significant palm trees framing the aedicule which sanctifies the scene. Limestone Coptic stele from Esna, Egypt.

The Peacock as Celestial Transport.

The splendiferous peacock, associated with the goddess Hera (the Roman Juno), came to the Mediterranean from India by way of Persia. It became an insignia for Roman empresses and other ladies of the imperial house. In Roman art, it was often shown in scenes of apotheosis, bearing the royal ladies up to heaven. In addition, because the flesh of the peacock was believed to be incorruptible, the peacock denoted immortality for Christians. The fanlike arc of the peacock's tail suggested gem-like stars and conformed so perfectly to arches, that the peacock served as an ideal architectonic metaphor for the heavenly vaults and the ascent into them.

Fig. 15. Soul Friends or Friends of the Departed: The earliest known Greek depiction of a peacock must have been carved shortly after the exotic bird was imported from Persia into such Greek lands as the Island of Samos where the cult of Hera prevailed.[3] In one rendition, a regal peacock grips two serpents, those time-honored chthonic symbols of earth's fertility and renewal as well as tutelary genii of the departed. Perhaps the snakes were intended to represent mates, since one of the pair is bearded and apparently crested. Chalcedony scaraboid gem of the mid-5th century BCE.

Fig. 17. DAPICS n. 2216. Apotheosis of a Royal Lady: On this obverse of an aureus of Julia, the daughter of the Emperor Titus, who was favored by her uncle Domitian, the peacock in display is surrounded by the legend: DIVI TITI FILIA ("daughter of the deified Titus"). Struck ca. 80 CE during the reign of Domitian.

Fig. 16. DAPICS n. 0120. Peacock on an Orb: A festoon is draped above the bird in profile, perched on an orb, insignia of the Roman Empire. Sprigs of roses embellish the scene. The twentieth-century graffiti are an example of the type of damage inflicted by careless visitors upon treasures of antiquity.[4] Rear wall painting in a chamber of the Catacomb of Vigna Randanini, Rome.

Fig. 18. DAPICS n. 0153. Peacock in Display: A frontal peacock spreads his tail. Vault painting in a chamber of the catacomb of Vigna Randanini, Rome.

Fig. 19. DAPICS n. 0121. Peacock amidst Roses: Painted wall of a chamber in the Catacomb of Vigna Randanini, Rome.

Fig. 21. DAPICS n. 0658. Peacock with lavish plumage: The elegant peacock turns away from the tree he dwarfs. Special attention is given to shadows in the summary rendering of a landscape. Vault painting, Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome.

Fig. 22. DAPICS n. 1792. Paradisiacal Bird in Residence: A peacock in profile appears to peck grapes in a grassy, floral setting under swagged festoons from which tassels composed of stylized clusters of grapes are suspended. Above this peacock's paradise, stars in concentric octagons and roundels, interspersed with encircled rosettes and sun-like configurations, are woven into a heavenly canopy. "And they that be wise shall shine as the brightness of the firmament; and they that turn many to righteousness as the stars for ever and ever" (Daniel 12:3). Celestial bodies were painted on the ceilings of Egyptian tombs as early as the period of the Old Kingdom. Badly-damaged painting in a double arcosolium next to a frescoed chamber in the upper catacomb below Villa Torlonia, Rome.

[1] Donna Kurtz and John Boardman, Greek Burial Customs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971), p. 238.

[2] James Breasted, Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912), p. 330.

[3] John Boardman, Greek Gems and Finger Rings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1970), pp. 198-199.

[4] During the Second World War, the cemetery was used as an air raid shelter.