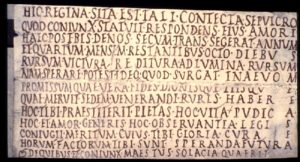

"Here lies Regina, covered by such a tomb which her husband set up as befitting his love. After twice ten years she spent with him one year, four months, and eight days more. She will live again, return to the light again, for she can hope that she will rise to the external life promised to the worth and the pious, a true assurance, being that she has deserved to possess an adobe in the hallowed land. This your piety has assured you, this your chaste life, this your love for your people, this your observance of the Law, your devotion to your wedlock, the glory of which was your concern. For all these deeds your hope of the future is assured. In this your sorrowing husband seeks his solace (1)."

Reaching across centuries, this poignant tribute of a mourning husband bears a timeless message of love, faith, and hope for life everlasting. Discovered in the Jewish catacomb of Monteverde in Rome, such a poetic example of epigraphy provides a fitting beginning to the study of the Roman catacombs - subterranean archives which yield a wealth of insight into the lives of those individuals whose remains are cradled in their depths, including polytheists (pagans), Jews, and Christians (2).

Regina's epitaph expresses the concern with mortality, the wish for immortality, and the desire for an appropriate ambiance for a permanent abode, concerns well documented in the catacombs of Ancient Rome (3).

Moses Gives Water to the Tribes (X, 27). Dura Europos Synagogue, West Wall, p. XII (Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period, Volume XI." Erwin R. Goodenough. Toronto: Pantheon Books, 1964. p. XII).

Giovanni Battista de Rossi, the pre-eminent nineteenth century explorer of Roma Sotterranea, characterized the underground cemeteries as the principal monuments of early Christianity remaining to us, and therefore the most important treasures of the nascent Church (4). In the same way the Jewish catacombs, with their relics and artifacts, add vital information to the limited documentary sources describing the Jews of ancient Rome, members of the oldest continuing Jewish community of Europe (5).

For the history of art as well, the catacombs provide important data, as do hypogea, the term for small private, or semi-private underground sepulchers constructed from natural or man-made cavities in the earth. Meant for one or several families, or a cooperative burial society, or adherents to a specific sect, both types of cemetery development house galleries that retain vestiges of Roman painting of the period, including examples of the symbolic or pictorial art of the followers of Judaism, Christianity, and other sects. The only other existing pictures of such significance for Judaism and early Christianity of the Late Roman period are to be found on the west bank of the Euphrates on the walls of the last phases of a third-century synagogue and baptistery at Dura-Europos, which offer an assemblage of Biblical and New Testament themes (6).

Catacomb paintings depicting basic rituals and giving visual expression to beliefs about the natural cycles of birth and death offered comfort in the face of man's realization of the inevitability of his own demise. While images in the Jewish and Christian catacombs of Rome were drawn from the visual repertoire of the contemporary Greco-Roman world, they had roots in much earlier Mediterranean cultures. Each community might interpret the figurations in the catacomb paintings according to its particular religious tenets, yet there was a great degree of common concern and sharing of spiritual concepts.

Detail of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego refusing to worship the golden image of Nebuchadnezzar, Catacombs of Marco and Marcelliano, Rome. DAPICS n. 2349.

Biblical themes were adopted in early Christian funerary iconography to express the hope of the deceased and their families for salvation and the felicity of the afterlife. Although Christianity gradually loosened its bonds with Judaism, the memory of its Jewish origins was never obliterate, subliminal though that memory may have become.

- Inscription 103 in D. Noy, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe 2: The City of Rome, pp. 85-88 = inscr. 476 in J-B. Frey, Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum 1: Europe, pp. 349-350 (B. Lifschitz, "Prolegomenon," pp. 37-38). Since this epitaph was written in metric form, Estelle Brettman chose to follow H. J. Leon's rather free translation in the Jews of Ancient Rome (no. 476, pp. 334-335) because of its poetic nature.

- Ancient catacombs have been found not only in Rome and various other parts of mainland Italy, Sicily, and Sardinia, but also in Roman North Africa, Cilicia, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Malta, and Mesopotamia.

- Fr. Antonio Ferrua, SJ, is one of the very few to believe that Regina's epitaph is Christian because of its lyrical and metrical form: "Sulla tomba dei cristiani e su quella degli ebrei," in La Civilta' Cattolica 87:4 (1936), pp. 307-309. But this marble slab, found in a Jewish cemetery, is engraved on just one side, and therefore not necessarily reused for a later burial. Poetic Jewish inscriptions have been found at Larisa (Greece), Leontopolis (Northern Egypt), and Beth She'arim: Lifshitz, "Prolegomenon," pp. 37-38. Virtue in the "observance of the Law," as expressed in this epitaph, is likely a Jewish concept.

- G. B. de Rossi, Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana 2.4 (1864), pp. 25-32.

- Extensive Jewish catacombs have also been discovered at Venosa in Italy and Beth She'arim in Israel. Small catacombs, hardly more than hypogea, have been found in or near Syracuse in Sicily, Sant'Antioco in Sardinia, Alexandria, Gammarth near Carthage, possibly Sabratha in anciet Tripolitania, Malta, Jerusalem, and in Syria, southeast of Palmyra.

- J. Guttmann, "Early Synagogue and Jewish Catacomb Art and Its Relation to Christian Art," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 2.21.2 (1984), pp. 1313-1335.

Note

The Jewish inscriptions will be identified in this book by the numbers assigned to them by David Noy in his two-volume compilation, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe 1: Italy, Spain, and Gaul (1993); and 2: The City of Rome (1995). Noy's numbers, prefaced by the abbreviation JIWE, will be followed by those in Jean-Baptiste Frey's publication, Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum 1: Europe (1936; reprinted in 1975 with a "Prolegomenon" by Baruch Lifshitz, who updated the Corpus at that time). Frey's numbers, in parentheses, will be identified with the designation CIJ. Harry Joshua Leon followed Frey's numbering in The Jews of Ancient Rome (1960). Frey and Leon have long been basic resources for the inscriptions and background of the Jewish catacombs of Rome and the history and structure of the Roman Jewish community. Contemporary study in the field has also benefitted greatly from such informed research and publication as Noy's work on inscriptions, Leonard V. Rutgers' The Jews in Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the Roman Diaspora (1995), and the many other accomplishments of the new generation of talented archaeologists and scholars in the field.